buildscript {

repositories {

maven {

url 'https://plugins.gradle.org/m2/'

}

}

dependencies {

classpath 'com.moowork.gradle:gradle-node-plugin:1.2.0'

}

}

apply plugin: 'com.moowork.node'

version = '1.0.0'

group = 'com.bmuschko'

node {

version = '9.8.0'

download = true

}

task helloWorld(type: NodeTask) {

dependsOn npmInstall

script = file('src/node/index.js')

}build docker container nodejs javascript gradle plugin March 28, 2018

The Gradle Docker plugin provides turnkey solutions to common use cases. In the previous blog posts of the series "Docker with Gradle", we looked at creating a Docker image for a Spring Boot application and how to use the image as fixture for integration testing. If you read the articles, you might have noticed that the plugin capabilities are flexible enough to model different situations. Nevertheless, this approach can easily become tedious if you want to use it across multiple, independent projects. Gradle promotes the idea of reusibility and encapsulation. Plugins embody the preferred way to implement those non-functionality requirements.

In this post, you will learn how to enhance the basic capabilities of the Gradle Docker plugin to establish conventions for your own projects. As an example, we will have a look at a very simpilistic Node.js application built and run by Gradle and packaged as Docker image.

To understand the content, you won’t need to have proficient knowledge of Node.js nor Javascript. The main objective of this post is to demonstrate the concept plugin composition and how to establish opinionated conventions. You can find the full source code on GitHub. I would recommend reading up on the most important design considerations and implementation concepts if you are just starting out with plugin development.

Building a Node.js application with Gradle

Gradle is a polyglot build tool and supports building other languages than just Java as long as there’s a plugin for it. The Node plugin supports the full lifecycle of a modern Javascript application. It even takes care of installing Node.js and NPM packages at runtime without manual intervention. The following build script shows how to apply the plugin and configure it to use a specific Node.js version. The script also adds a task for executing a Node.js script as the main entry point.

application/build.gradle

Listing 1. Applying and configuring the Gradle Node plugin

The task helloWorld points to the Javascript file src/node/index.js when executed. Judging by the name, it should print a "Hello World" message to the console. The index file uses the NPM package figlet to make the output visually appealing.

application/src/node.index.js

const figlet = require('figlet');

var out = figlet.textSync('Hello World!', {

font: 'Standard'

});

console.log(out);Listing 2. A simple Node.js application

Executing the task produces the following output.

./gradlew helloWorld

> Task :helloWorld

_ _ _ _ __ __ _ _ _

| | | | ___| | | ___ \ \ / /__ _ __| | __| | |

| |_| |/ _ \ | |/ _ \ \ \ /\ / / _ \| '__| |/ _` | |

| _ | __/ | | (_) | \ V V / (_) | | | | (_| |_|

|_| |_|\___|_|_|\___/ \_/\_/ \___/|_| |_|\__,_(_)

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 3s

3 actionable tasks: 1 executed, 2 up-to-dateNeat, you got your first Node.js application up and running without having to resort to a Javascript-based build tool like Grunt or Gulp.

Let’s also inspect the application’s package.json file. As you can see in the listing below, we provided a name, a version and a description for the application. Most importantly, the file also declares the NPM dependency. Now, it’s a good idea to also check in a package lock file to ensure that the same dependency version is resolved whenver the build is executed.

application/package.json

{

"name": "nodejs-hello-world",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "Prints hello world message",

"private": true,

"license": "Apache License 2.0",

"repository": {

"type": "git",

"url": "https://github.com/bmuschko/gradle-docker-convention-plugin"

},

"dependencies": {

"figlet": "^1.2.0"

}

}Listing 3. The application’s package file

So far the application has no touch point with Docker. In the next section, you will set up the infrastructure for building a Gradle plugin for the purpose of creating a Docker image for the application and pushing it to DockerHub.

Creating the basic plugin infrastructure

It’s a good idea to implement a Gradle plugin as a standalone project to simplify the process of publishing it to a binary repository later. As part of this blog post, you are only going to build the plugin as part of a composite build. Usually, you’d go the additional mile and publish the artifact(s) so that it can be reused by other, independent projects. The following directory structure separates the plugin implementation from the actual application using it.

$ tree . ├── application └── plugin

Getting started with writing a plugin looks very similar in most cases: create a build.gradle file, apply the Java Gradle Plugin Development plugin and declare any dependencies needed to build the project.

In this case, you will also want to build upon the capabilities provided by the Gradle Docker plugin. The build script declares a dependency on version 3.2.5. You might have guessed that the plugin code will be writting in the language Groovy as the groovy plugin has been applied as well.

plugin/build.gradle

apply plugin: 'groovy'

apply plugin: 'java-gradle-plugin'

version = '0.1'

group = 'com.bmuschko'

ext.compatibilityVersion = '1.6'

sourceCompatibility = compatibilityVersion

targetCompatibility = compatibilityVersion

repositories {

jcenter()

}

dependencies {

compile 'com.bmuschko:gradle-docker-plugin:3.2.5'

}Listing 4. Setting up the plugin’s build script

Implementing the plugin class

Let’s talk about the requirements for the plugin before we get down to the actual implementation. In a nutshell the following aspects should be covered:

-

The plugin should be able to use task types provided by the Docker plugin.

-

The workflow should be able to create a Dockerfile, build an image and push it to DockerHub.

-

The plugin should introduce conventions so that the user can work with sensitive defaults.

-

A user should be able to configure essential runtime behavior like the base image or the exposed ports of the container.

Listing 5 shows a plugin class that fulfills all of those requirements.

DockerNodeJsApplicationPlugin.groovy

package com.bmuschko.gradle.docker

import com.bmuschko.gradle.docker.tasks.image.DockerBuildImage

import com.bmuschko.gradle.docker.tasks.image.DockerPushImage

import com.bmuschko.gradle.docker.tasks.image.Dockerfile

import org.gradle.api.Plugin

import org.gradle.api.Project

import org.gradle.api.tasks.Sync

class DockerNodeJsApplicationPlugin implements Plugin<Project> {

public static final String NODE_JS_APPLICATION_EXTENSION_NAME = 'nodeJsApplication'

public static final String DOCKERFILE_TASK_NAME = 'createDockerfile'

public static final String SYNC_DIST_RESOURCES_TASK_NAME = 'syncNodeFiles'

public static final String BUILD_IMAGE_TASK_NAME = 'buildImage'

public static final String PUSH_IMAGE_TASK_NAME = 'pushImage'

@Override

void apply(Project project) {

project.apply(plugin: DockerRemoteApiPlugin)

DockerExtension dockerExtension = project.extensions.getByType(DockerExtension)

DockerNodeJsApplication dockerNodeJsApplication = dockerExtension.extensions.create(NODE_JS_APPLICATION_EXTENSION_NAME, DockerNodeJsApplication)

Dockerfile createDockerfileTask = createDockerfileTask(project, dockerNodeJsApplication)

Sync distSyncTask = createDistSyncResourcesTask(project, createDockerfileTask)

createDockerfileTask.dependsOn distSyncTask

DockerBuildImage dockerBuildImageTask = createBuildImageTask(project, createDockerfileTask, dockerNodeJsApplication)

createPushImageTask(project, dockerBuildImageTask)

}

private Dockerfile createDockerfileTask(Project project, DockerNodeJsApplication dockerNodeJsApplication) {

project.task(DOCKERFILE_TASK_NAME, type: Dockerfile) {

description = 'Creates the Docker image for the Node.js application.'

from { dockerNodeJsApplication.baseImage }

copyFile('package*.json', './')

copyFile('index.js', '/index.js')

runCommand('npm install')

entryPoint('node', 'index.js')

exposePort { dockerNodeJsApplication.ports }

}

}

private Sync createDistSyncResourcesTask(Project project, Dockerfile createDockerfileTask) {

project.task(SYNC_DIST_RESOURCES_TASK_NAME, type: Sync) {

description = "Copies the distribution resources to a temporary directory."

from('.') {

include 'package*.json'

}

from 'src/node'

into createDockerfileTask.destFile.parentFile

}

}

private DockerBuildImage createBuildImageTask(Project project, Dockerfile createDockerfileTask, DockerNodeJsApplication dockerNodeJsApplication) {

project.task(BUILD_IMAGE_TASK_NAME, type: DockerBuildImage) {

description = 'Builds the Docker image for the Node.js application.'

dependsOn createDockerfileTask

conventionMapping.inputDir = { createDockerfileTask.destFile.parentFile }

conventionMapping.tag = { dockerNodeJsApplication.getTag() }

}

}

private void createPushImageTask(Project project, DockerBuildImage dockerBuildImageTask) {

project.task(PUSH_IMAGE_TASK_NAME, type: DockerPushImage) {

description = 'Pushes created Docker image to the repository.'

dependsOn dockerBuildImageTask

conventionMapping.imageName = { dockerBuildImageTask.getTag() }

}

}

}Listing 5. The convention plugin implementation

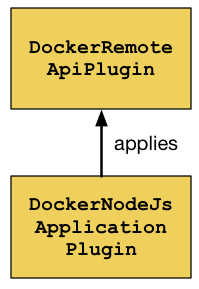

We will disect the most important aspects of this rather lengthy code snippet. First of all, the plugin applies the DockerRemoteApiPlugin which brings the basic Docker capabilities. Most of the tasks created by the plugin rely on the task types introduced by the Docker plugin.

Figure 1. Building upon the capabilities of the Docker plugin

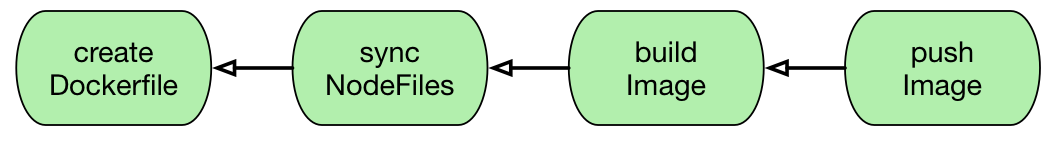

The plugin creates four tasks and establishes the proper dependencies between them to form a meaninful lifecycle. For example, executing the task pushImage takes care of building the image first.

Figure 2. The tasks and their dependencies created by the plugin

-

createDockerfile: Creates the Dockerfile using default conventions. -

syncNodeFiles: Synchronizes the Node.js files of the application with a target directory for packaging. -

buildImage: Builds the image of the Node.js application from the Dockerfile. -

pushImage: Pushes the image to DockerHub.

You might be familiar with the concept of convention mapping used by this plugin. Convention mapping is an internal Gradle API which allows plugin developers to defer the evaluation of a property value until it is actually needed. At the time of writing, the Docker plugin does not use the public and recommended Provider API yet. For more information, follow this issue.

Exposing a custom DSL for configuring runtime behavior

Plugins should give users the ability to reconfigure default conventions if they don’t fit the project’s needs. The extension DockerNodeJsApplication exposes a custom DSL for configuring the base image, exposed container ports and the tag used for the produced image. As you can see in listing 6, most properties already come with a default value.

DockerNodeJsApplication.groovy

package com.bmuschko.gradle.docker

class DockerNodeJsApplication {

String baseImage = 'node:9'

Set<Integer> ports = [8080]

String tag

}Listing 6. The extension exposed by the plugin

The plugin implementation in listing 5 registers the DockerNodeJsApplication extension. You might not have noticed that the extension hooks into the existing Docker plugin extension. It creates an extension for an extension. That may sound complicated but leads to a seamless enhancement of the existing Docker plugin DSL.

DockerExtension dockerExtension = project.extensions.getByType(DockerExtension)

DockerNodeJsApplication dockerNodeJsApplication = dockerExtension.extensions.create(NODE_JS_APPLICATION_EXTENSION_NAME, DockerNodeJsApplication)Listing 7. Enhancing the extension of the Docker plugin

Next, you will see how simple the actual build script looks like to the end user.

Using the plugin in the application project

It’s time to bring it all together. At the moment the plugin is not available on the Gradle plugin portal though I am considering making it part of the Docker plugin suite if more people are interested. Let me know what you think!

application/build.gradle

buildscript {

repositories {

maven {

url 'https://plugins.gradle.org/m2/'

}

}

dependencies {

classpath 'com.bmuschko:gradle-docker-nodejs-plugin:0.1'

}

}

apply plugin: 'com.bmuschko.docker-nodejs-application'

docker {

registryCredentials {

username = getConfigurationProperty('DOCKER_USERNAME', 'docker.username')

password = getConfigurationProperty('DOCKER_PASSWORD', 'docker.password')

email = getConfigurationProperty('DOCKER_EMAIL', 'docker.email')

}

nodeJsApplication {

tag = "bmuschko/nodejs-hello-world:$project.version"

}

}

String getConfigurationProperty(String envVar, String sysProp) {

System.getenv(envVar) ?: project.findProperty(sysProp)

}Listing 8. A build script applying and configuring the Docker Node.js plugin

Let’s see the process in action. For the purpose of demonstration you can use composite builds to skip the step of publishing the plugin to a binary repository. Just navigate to the directory application and run the command ./gradlew --include-build ../plugin pushImage.

Conclusion

Implementing a convention plugin has a lot of benefits. First of all, the plugin encapsulates complex and imperative logic. As a result, the consuming build script becomes less cluttered with implementation details. Default conventions provide sensible defaults applicable to most users. Declarative custom language elements expose an "user interface" to control the runtime behavior and can seemlessly blend in with the Gradle core DSL.